! Buy the new book !

The Way Home:

A Photo Biography of AD Hasler

by A Frederick Hasler

from the createspace store for $23.70

Professor Arthur Davis Hasler, PhD

The Way Home:

A Photo Biography of AD Hasler

by A Frederick Hasler

now available on line…... from the link:

Tributes to Arthur Davis Hasler and The Way Home, A Photo

Biography by his son Fritz (Arthur Frederick Hasler)

Arthur D. Hasler was one of the foremost

limnologists of the 20th century, but there are many more elements to his rich

and fascinating life: beyond his work in limnology and animal behavior and his

University of Wisconsin career, Hasler was a Germanophile who served America in

Germany in World War II, a family man, and a lifelong Mormon. His son Arthur F. Hasler’s new

book The Way Home uncovers many aspects of his

multidimensional life and recounts them with a spectacular collection of large,

high quality black & white and color photographs.

Lynn K.

Nyhart,

Vilas-Bablitch-Kelch

Distinguished Achievement Professor

Department of the History of Science, University

of Wisconsin-Madison

In my book The Dancing Bees

- 2016, the story of Arthur D Hasler is woven inextricably into the

life of Karl von Frisch. It is wonderful to see their interaction so richly

illustrated through photographs and archival documents in The Way Home,

the 2017 book by his son Arthur F. Hasler. Hasler’s

contributions to science were significant, and he continues to hold a special

place with family, friends, students, and colleagues who remember a life

well-lived.

Tania Munz,

author of The Dancing Bees, Karl von

Frisch and the discovery of the Honeybee Language

VP for Research and Scholarship, Linda Hall Library of Science,

Engineering & Technology, Kansas City, Missouri.

As

Arthur Davis Hasler’s last graduate student, I would like to describe what it

was like to work with this scientific giant of a man and convey what his 53

Ph.D. students felt about him. Herr Doktor Professor Hasler, or more

affectionately “Doc” as he was called by the cadre of students with whom I was

associated, was unanimously appreciated for both his scientific rigor and

helpful advice that he freely gave to us. We admired and respected him. He

prepared us so well, and all his students were so highly thought of by the

scientific community, that within 3 months of our graduation, almost all of us

had either a teaching or research position at another university.

Fritz’s

book captures the entire life of Arthur Davis Hasler and provides rare sagacity

into how and why scientific discoveries are made. The book also presents Arthur

Davis Hasler family man and community/political activist. Finally, it provides

insight into the central role of the University of Wisconsin in developing the

science of limnology.

I

thought Fritz did a wonderful job of integrating his dad’s scientific

accomplishments with his family history. I was particularly impressed with Chapter

7 that covered Doc’s role in the U.S. War Department’s 1945 Strategic Bombing

Survey in Germany and Austria. Excerpts of his letters to his wife and children

were illuminating, capturing the extent of the devastation wrecked upon the

allied bombing of these Axis countries. The chapter also describes Doc’s

meeting with Nobel Laureate Karl von Frisch, who discovered the dance language

of honey bees, whereby bees communicate the direction and distance to sources

of nectar to other bees in the hive. In a letter home, Doc included a

description of witnessing one of von Frisch’s experiments, which for me was the

highlight of the book.

Allan T. Scholz,

Emeritus Professor of

Biology (Fisheries), Eastern Washington University

Cheney,

Washington May 5, 2017

A remarkable photographic

portrayal (and tribute) to a remarkable scientist, Arthur D. Hasler.

This unique, thoughtful and loving memoir fills in much important

information about one of the key leaders in the long and important history of

limnology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. A must read for anyone

interested in the history of aquatic ecology in general and especially of

limnology at the University of Wisconsin. Many aspects of Art’s life and

scientific achievements are reported in this book. It will serve as an excellent reference document for Limnology in Wisconsin during the Hasler era.

Dr. Gene E. Likens,

University of Connecticut, Special Advisor to the President on

Environmental Affairs

Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, Founding

Director and President Emeritus, Millbrook, New York.

Led a team that discovered Acid Rain, 1963

Elected a member of the National Academy of Sciences, 1981

National Medal of Science Award winner, presented by President George W. Bush, 2001

From the UW Center for Limnology

What an amazing and

wonderful tribute to Arthur Davis Hasler. The

Way Home, a photo biography created by his oldest son, Arthur Frederic

(Fritz) Hasler captures both the profession and the family of Arthur, the

scientist and the father. The Way Home

hints at the importance of his family and details Art’s major contribution of

learning how migrating salmon find their way home to spawn. Arthur, like many

scientists and fathers, had these two families -- his genetic family of

parents, children, and their descendants, and a professional family of

scientific programs, graduate students and colleagues, and their descendants.

Arthur was devoted to both families. He succeeded admirably in both roles.

Today Arthur Davis Hasler is appreciated and honored by each of these important

populations.

Clearly, the author

and son, Fritz, loved Art, and he honored, respected, and admired Art as a

professional scientist and educator. These elements permeate the photo

selection and brief text that accompanies each photo. Our perception is that

Fritz learned a great deal about his scientist father as he discovered

photographs and new aspects of Art’s life. For Fritz this has been a process of

collecting his and the family’s memories and discovering new revelations about

Art that took place after he, Fritz, had left home. Many members of Art’s

genetic family helped with photos and memories. Similarly, members of Art’s

professional family helped to find photographs and contributed their memories.

Archives maintained by the University of Wisconsin were important to this

endeavor. Fritz’s enthusiasm and skill with visual images had developed as a

professional analyst of satellite images with NASA for 30 years.

This, then, is a

juxtaposition of Art’s personal family life with his professional life as a

scientist and educator. It becomes obvious that both are related and

intertwined through time. Professional colleagues will discover the family

behind the man and what appeared to have driven his approach to science and its

application to human concerns about water organisms and ecosystems. The family

will discover, as did Fritz, the contributions that Art made to doing cutting-edge

science, educating the next generations of scientist and educators, building

and fostering scientific institutions, and addressing local to global

environmental and scientific challenges.

John

J. Magnuson, Founding Director of the Center for

Limnology (Emeritus)

James

F. Kitchell, Director of the Center for

Limnology (Emeritus)

and

Stephen R. Carpenter, Director of the Center for

Limnology

University

of Wisconsin-Madison

May 2, 2017

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++Professor Arthur Davis Hasler, PhD

Zoologist, Limnologist, Ecologist

University of Wisconsin Madison

Professional Photo Biography by son Fritz Hasler

This Blog Post is sponsored by a member of the Hasler Family

A series of photos and documents of Art's professional life, arranged mostly chronologically with explanations and commentary by me, other family members and colleagues.

This Blog Post is sponsored by a member of the Hasler Family

A series of photos and documents of Art's professional life, arranged mostly chronologically with explanations and commentary by me, other family members and colleagues.

Sources: Art's family color slide collection, Limnology Laboratory Archive images, Power Points by John Magnuson, his first wife, Hanna's, family photo album, University of Wisconsin Archives, The negatives of Art's photographs from Europe in 1945, Art's lecture slide carousel, digital photos that I took after 2000, related images from the internet, and a biography of ADH by Gene Likens (included at the end). Various family photos. often taken by Art, are added for context. John Magnuson (Emeritus Director of the Limnology Lab, David Null (Director of the University of Wisconsin Archives) Daughter Sylvia and son Galen have been very helpful in collecting and scanning photographs. All of Art's children have been helpful in assembling material, adding anecdotes, and making corrections.

Art, Lago Maggiore, 1955

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

Biographical Synopsis

From my memories, Art's genealogy, and a biography by his student, Gene Likens

Note: the Gene Likens biography and a biography by his last student, Allan T. Scholz appear in a separate post in this blog

Arthur learned to play the French horn in high school and continued to play throughout his life including 20 years for the University of Wisconsin Symphony and the Madison Civic symphony. Arthur was very active in the Boy Scouts of America and received the Eagle badge in 1924. Arthur served a 30 month mission for the LDS (Mormon) Church to Germany, Czechoslovakia and Austria, from July 1927 to February 1930. He learned the German language very well on his mission and continued to study and love it for the rest of his life. He graduated from BYU in 1932 and married Hanna September 6 1932 in SLC. They left directly for the University of Wisconsin in Madison when Art began his graduate studies in Zoology. In 1935 he took a job with the US Fish and Wild Life Service on the Chesapeake Bay and worked for two years while living in York Town Virginia, where Sylvia was born.

He returned to the University of Wisconsin in 1937 to finish his PhD in Zoology and begin as an instructor in the department. He was promoted to Assistant Professor in 1941, Associate Professor in 1945, and Full Professor in 1948. He served on the Strategic Bombing Survey in Germany for four months in 1945 for the U.S. Army Airforce. 52 doctoral students (a full deck) and 43 masters students received their degrees under his supervision His research study that brought him the most acclaim was the scientific proof that salmon learn the odor of their birth stream as smolts (fingerlings) and find their way back to the that same stream 1.5 to 5 years later as adults by the use of the sense of smell. He worked on and refined that study from 1945 through the end of his career in 1983. He wrote and coauthored over 200 peer reviewed scientific papers and authored or contributed to seven books. In 1954 and 1955 he went on a one year sabbatical as a Fulbright Research Scholar at the University of Munich Germany with famous honeybee researcher and Nobel Prize Winner, Professor Karl von Frisch.

He wrote the proposals and received funding from the National Science Foundation to build the Laboratory for Limnology at the University of Wisconsin in 1963. He was elected as a member of the National Academy of Sciences in 1969. In American scientific circles this is an honor short only of winning the Nobel prize. He also received numerous other awards and honorary degrees from other Universities. He received funding for another research lab, this one on his beloved Trout Lake in Northern Wisconsin. He retired in 1978. In 2006 he received the post humus honor of having his lab renamed the Arthur D Hasler Laboratory of Limnology. He survived four different kinds of cancer including, colon, neck, and lung starting in 1972. The three malignant cancers of the colon, lung and lymph glands were treated by undergoing two major surgeries and chemotherapy. He died March 23, 2001 of old age.

Figure 1: Walter T and Ada Hasler, Provo 1933

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Figure 2: Hasler Children, Provo, 1915

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Art's older brother, Thalmann (Tommy) went medical school and became a doctor like his father.

Art graduated from college at the height of the depression and with his father suffering from cancer, there was not enough money in the family to send him to medical school like his brother.

Hundreds attended his funeral in Madison.

Figure 1: Walter T and Ada Hasler, Provo 1933

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Arthur Davis Hasler was born on January 5, 1908 to Walter Thalmann Hasler and Ada Elizabeth Broomhead in Lehi Utah.

WT Hasler was the son Swiss immigrants. His father was a musician who brought music education to the small town of Mt Pleasant in north central Utah.

Walter was the first in his family to pursue higher education. He attended the Baltimore College of Physicians and Surgeons (Now the University of Maryland School of Medicine) received his MD degree, and practiced as an Eye, Ear, Nose, and Throat Specialist in Provo Utah for many years.

Figure 2: Hasler Children, Provo, 1915

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Bill, Ada, Art (7), Thalmann, Calvert just after having moved from Lehi, to Provo Utah.

Art's oldest brother Calvert died of diabetes at the age of 16 in spite of his doctor father's best efforts in the days before insulin was discovered.

Art's older brother, Thalmann (Tommy) went medical school and became a doctor like his father.

Art graduated from college at the height of the depression and with his father suffering from cancer, there was not enough money in the family to send him to medical school like his brother.

As a result, Art applied for a graduate assistantship at the University of Wisconsin in the Zoology Department, and the rest is history (see Figure 9 etc.)

Figure 3: Art with other Eagle Scouts, Provo, 1924

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Middle row right wearing Eagle Pin on his left pocket at age 16 (see the pin on his eagle sash - Figure 183)

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Art age 19, Freshman at BYU Provo

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Art's LDS Mission to Germany and Austria

where he learned German

Figure 6: Art, On his 30 month LDS Mission, Germany, 1928

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Art served a two-and-one-half year mission for the LDS (Mormon) Church in Germany, Czechoslovakia, and Austria from 1927-29.

Dad worked diligently studying German and learned it well. He loved German and the German people and defended them even when Germany wasn't popular in the U.S.

I don't know how many times I heard him say this:

"Meine Beziehung zu der deutschen Sprache ist zu meiner Frau, ich kenne sie, ich liebe sie, aber ich beherrsche sie nicht."

I dictated it to my iPhone using the German keyboard that makes-up for my poor German spelling.

English translation: "My relationship with the German language is the same as the one I have with my wife. I know her, I love her, but I don't rule her"

Art returned to BYU in the Fall of 1929 and graduated with a BS in Zoology in 1932. His study of Utah high Uinta mountain lakes during his zoology studies got him interested in limnology.

(UW-Madison Archives)

His son Galen found this in the University of Wisconsin Archives along with a complete record of his correspondence through the years. From the stamps on the passport we know that Art landed in Liverpool England on July 23 1927, served his mission in Germany, Czechoslovakia and Austria. This passport expired May 23, 1929, but it must have been extended and he probably returned in February of 1930 for a total time served of 30 months. Also note that at 21 he gave his height at 5' 10" He must have matured very late to 6'. In his letters from Salzburg and Linz Austria in 1945 he recalls serving there 15 years earlier on his mission.

Figure 8: District President Hasler, Vienna, Jan 1929

Inscription:

"Pres Hasler des Öestereichischen Distrikts"

(President Hasler of the Austrian District)

Professionally dad was somewhat embarrassed by this part of his resumé. When asked about his mission, he would emphasize the work he had done in Germany to promote the Boy Scout program of the LDS Church. However as you can read in this history, you can see that dad served in very important leadership positions on his mission and could have emphasized that part of his service.

He was also the District President (chief ecclesiastical administrator) for all the Mormons in Vienna Austria and for Breslau East Germany (now part of Poland) during different periods on his mission.

Figure 9: President Hasler, Colleagues, Breslau, October 1929

By this time Art was District President for the 2nd time, now for the city of Breslau and surrounding See him here (First row 2nd from left)with the President of the German Austrian Mission, Hyrum W Valentine, visiting from Dresden.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Art comes back to Utah and finishes his BS Degree in Zoology

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Art Marries Hanna Prusse and goes to UW Madison for Graduate School

Figure 10: Art marries Hanna Prusse, Provo, 1932.

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Formal Wedding picture: Hanna Bertha Prusse and Arthur Davis Hasler

If you knew Art professionally, you also knew how important his wife Hanna was to his professional career.

Art and Hanna were married on September 6, 1932 in the historic Salt Lake Temple. Her sisters Irmgard (left center) and Eveline (right), who were tiny girls on the immigrant boat (from Hanover Germany to Galveston) with her in 1913, were her maid of honor and one of the bridesmaids. Art's brother Bill was the best man.

Figure 11: Art's Graduate School Application, Madison, 1932

(UW-Madison Archives)

“Hanna and Arthur were married September 6, 1932, in the Salt Lake Temple and they left immediately for graduate school in Madison, Wisconsin”

Figure 11: Art's Graduate School Application, Madison, 1932

(UW-Madison Archives)

“Hanna and Arthur were married September 6, 1932, in the Salt Lake Temple and they left immediately for graduate school in Madison, Wisconsin”

Figure 12: Newlyweds Art and Hanna, Milwaukee, 1933.

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

This is the first picture we have of the newlyweds in Wisconsin. It was taken in front of the LDS Church in Milwaukee, in 1933 when they were both 25.

Figure 13: Art & Hanna, Madison ,1933

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Art and Hanna arrive on the University of Wisconsin Campus from Utah

(Bascom Hall in background)

Art and Hanna were married for 37 years from 1932 until Hanna's death in 1969 at the age of 61.

Figure 14: Hanna, Old Lake Lab, Madison, 1933

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Hanna on the pier ready to go fishing with Art on Lake Mendota.

Figure 15: Art's Fishing License, Door County, 1933

(Fritz Hasler family heirloom)

Even the future fish professor had to have a fishing license to fish legally in Wisconsin. By 2016 I think the price of a fishing license, even for In-State Residents had increased a bit.

Figure 16: The Big Three - Birge, Juday, Hasler

(Cover: Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences)

Birge, Juday, and Hasler pioneered Limnology at the University of Wisconsin Madison.

Cover of Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts & Letters - Special Issue Breaking New Waters A Century of Limnology at the University of Wisconsin - 1987. The book recounts the history of the work by Birge, Juday and Hasler.

Edward A. Birge 1851-1950 (Life span 99 years)

Chancy Juday 1871-1944 (Life span 73 years)

Arthur D. Hasler 1908-2001 (Life span 93 years)

Figure 17: Birge, Juday, Trout Lake, 1930

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Edward A. Birge and Chancey Juday at the Trout Lake Research Station.

Birge found time to work with his students after retiring from his responsibilities as President of the University of Wisconsin Madison (1918-1925). Birge, Juday, and Hasler were members of the Zoology department at the University that is housed in Birge Hall.

However, in Art's oral history, he describes Birge at this point in his career as flitting in for a couple of days, a few times during the summer, driven in by a UW limousine, probably a perk he retained as a former president of the University.

Figure 18: Birge, Crystal Lake, 1930

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Birge near Trout Lake, with the "sun machine" on top of his car

Figure 19: Birge, Baum, Trout Lake, 1933

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Birge and Hugo Baum, with the "sun machine" just down the shore from the Trout Lake Camp

According to Art's oral history, Birge is measuring light penetration into the water.

Figure 20: Art, Baum, Trout Lake, 1933

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Hugo Baum and Art building "Lime Floats" at the Trout Lake Camp.

Arthur D. Hasler, the third member of the Big Three is just a graduate student working with Juday at this point. He won't receive his PhD until 1937 and won't become a full professor until 1948.

I'm guessing that Baum is sitting on a finished "Lime Float" designed to release lime from the barrel slowly into the water.

Figure 21: Trout Lake Camp, 1933

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Figure 22: Trout Lake Camp, 1933

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Students,Trailer, Boats, Motors

Today in 2016, the pier and the cabins of the Trout Lake Camp on South Trout have been gone for decades, but the beach is now a public picnic area that anyone can visit. Subtract the pier, boats and trailer and it looks 83 years ago very much like it does today.

Go North from Woodruff on 51, turn right on M, turn left at the first Trout Lake Forestry Head Quarters entrance. Just beyond the bike trail on the left is a place you can turn in and park. Continue 200 yards on the path down to Trout Lake.

Figure 23: Art, Juday, other Students, Trout Lake, 1933

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Summer of 1933 at the Trout Lake Research Station in Northern Wisconsin

Art top, second from left, Chauncy Juday bottom, third from left

Front row from left: Hugo Baum, Edward Schneberger, C. Juday, Sam X. Cross, Militzer and William Spoor

Back row from left: Ray Lanford, A. D. Hasler, Robert Hunt, V. W. Meloche, and Harold Schemer.

Identifications by Mrs. Juday 1956

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Summer of 1933 at the Trout Lake Research Station in Northern Wisconsin

Art top, second from left, Chauncy Juday bottom, third from left

Front row from left: Hugo Baum, Edward Schneberger, C. Juday, Sam X. Cross, Militzer and William Spoor

Back row from left: Ray Lanford, A. D. Hasler, Robert Hunt, V. W. Meloche, and Harold Schemer.

Identifications by Mrs. Juday 1956

Figure 24: Juday, Art, Birge, Students, Trout Lake, 1934

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Professors Edward A. Birge, and Chauncy Juday, with graduate students including Art Hasler third from the right. Chauncey Juday is in the center in the dark coat. Art studied Lake Mendota from the shores of the UW campus and the lakes in Northern Wisconsin as part of his graduate studies.

From the left: David Frey, Martin Baum, John Schreiber, Don Kerst, Harold Shomer, C. Juday, E. B. Fred, Richard Juday, A. D. Hasler, Paul Pavcek and E. A. Birge.

Figure 25: Putting in a boat, Trout Lake, 1934

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Trailing a boat was a little more primitive in those days, but they already had the idea. Note: Outboard on the car windowsill, and the oars on the running board.

Figure 26: Fyke Nets, Trout Lake Camp, 1934

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Fyke Nets were used for catching yellow perch,

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Art leaves school and takes a job with the US Fish and Wild Life Service in York Town VA

Figure 27: Art, Oyster Apparatus, Yorktown, 1935

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Art had left the University of Wisconsin in 1935 before he finished his dissertation, to take a job for two years with the US Fish and Wild Life Service in York Town, Virginia

Figure 28: Art, US BF Lab, Washington DC, 1936

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Art doing Glycogen Analyses at the U. S. Bureau of Fisheries Lab in Washington DC during his two year stint in York Town VA.

Figure 29: Prusses + Arthur & Sylvia, Provo,1937.

(Hasler Family Album, scanned from Bill Prusse Negative)

Spring 1937: The first grandchild joins the Prüsse Clan.

Art, Hanna, & baby Sylvia upper right.

Art's wife Hanna was the eldest of 13 children. Her father, baker Wilhelm Prusse, brought his wife and the first five children from Hanover Germany to SLC in 1913 just before the start of WWI

Art, Hanna, & baby Sylvia upper right.

Art's wife Hanna was the eldest of 13 children. Her father, baker Wilhelm Prusse, brought his wife and the first five children from Hanover Germany to SLC in 1913 just before the start of WWI

In this picture, the Haslers had just made the long trek west to Utah from Yorktown Virginia to attend a Prusse family reunion. They probably came by car, taking over a week on the road with a stop in Madison, in the days before freeways. They brought their first child, Sylvia, born October 4th 1936, and the first grandchild of Wilhelm & Johanne to meet them and Sylvia’s 13 aunts and uncles.

Figure 30: Art, Rangers, Crater Lake NP, 1937

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Art and other Rangers at Crater Lake National Park in Oregon.

It's all making sense now. Art keeps heading west to take a summer job on the west coast as a ranger and Hanna stays behind with her folks in Utah with one-year-old Sylvia.

Figure 31: Ranger Art, Big Fish, Crater Lake, 1937

(Center for Limnology Archives)

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

In the Fall he started his job as an Instructor at the University of Wisconsin in Madison and finishes his PhD.

Figure 32: Chauncy Juday, Madison, 1937

(UW-Madison Archives)

Art gets his PhD in 1937 on the physiology of digestion of plankton Crustacea (including Daphnia) from Chauncy Juday

Figure 33: Art, Madison Civic Symphony, 1938

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Art, back row right with the French Horn to the right of the right bass player.

When he is not working for the US Government in Virginia, the National Park Service in Oregon, working on his PhD, teaching students, doing his research, raising a family, or driving his family to Utah, Art begins his 20 year career playing the French horn with the Madison Civic Symphony and the University of Wisconsin Symphony.

Figure 34 Art, with French Horn, Madison

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Art's whole family was musical, practically the von Trapp family singers.

This picture was taken in 1953, inserted here to show Art close-up with his French Horn.

Back Row: Galen, Bruce, Karl, Hanna, Fritz, Art

At the Piano: Sylvia, Mark

Hanna helped dad in so many ways throughout his career. That included performing for his professional guests

Figure 35: Art, Birge Hall, Madison, 1940

(Hanna & Art Family Album)

Probably Birge Hall.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Art Joins the US Army Strategic Bombing Survey and Spends 5 months in Germany and Austria

He Meets Nobel Prize Winner. Karl von Frisch, in Austria

Figure 37 Art & Colleague Somewhere in Europe May1945

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

In 1945, just before the Nazis surrendered, Art volunteered for the Strategic Bombing Survey with the US Army in Germany. Using his German language skills he interviewed German civilians to determine the effectiveness of the indiscriminate bombing and complete destruction of German cities including civilian populations by high explosives and firebombing during the war.

Today we would call this "a crime against humanity".

The Survey determined that the the bombing of civilian populations did not break their will, and may even have strengthened their bond with the Nazi government.

The US went on firebombing Japanese cities, including Tokyo.

The Nazis had started bombing civilians in Guernica Spain(subject of Picasso's famous painting) during the Spanish civil war and continued on with aircraft and missile bombing of civilians in London during the battle of Britain. Therefore it is not surprising that the allies responded with bombing of civilian populations in Germany. Astonishingly, no one repeated the horrible chemical warfare from WWI.

After a search of family archives (where we found his letters from Germany), the Limnology Lab, the UW-Madison Archives at the Steenbock Library, we finally found Art's negatives from his photographs of Europe in 1945 in an off-site Limnology storage facility in Stoughton. We have still not found his photo album from the trip.

On May 7, 1945 Art landed in Paris on VE day as a volunteer..... (Documented in his letter to Hanna. "The whole plane wondered why Paris was crazy celebrating". They could not make London due to weather and arrived the next day when London was celebrating. "The English waited a day" he commented in his letter) The timing is another amazing happenstance of his lucky life.

Figure 38: Darmstadt Following RAF Firebombing, 1944

(Sept 1944, Found on the Internet)

(Sept 1944, Found on the Internet)

Art arrived in Europe on VE day, May 8, 1945. We were finally able to locate the photos he took and we have the almost daily letters he wrote home from May through August 1945. He spent his first night in Paris and then witnessed the VE celebrations on May 9th in London the next day. He spent the first 6 days in London getting trained and outfitted then traveled two days by plane and jeep to his first duty station in Darmstadt Germany.

Darmstadt had been firebombed during RAF raids on the night of the 11th and 12th of September 1944 that decimated the city and killed over 14,000 residents. So when dad arrived there eight months later, he got to see the results and hear firsthand the stories of those terrible days.

Figure 39: Corpus Christi Procession, Munich, 11 June 1945

(Found on the Internet)

Frauen Kirche and battered Munich.

Frauen Kirche and battered Munich.

Art went through Munich only 10 days earlier and must have seen the central city much as it appears here. Miraculously the towers of the iconic Munich Frauen Kirche survived the bombing.

He saw firsthand the terrible destruction of Darmstadt and Stuttgart and must have seen what we see above. We know that von Frisch expected that his house in the suburbs would be safe even if his lab at the Universität München built by the Rockefeller Foundation was in danger. Art visited the partially destroyed lab on June 2nd. von Frisch moved his extensive library on animal physiology to his home. Unfortunately his house suffered a direct hit, The house and library were completely destroyed except for a milk can hanging in a nearby tree. von Frisch moved to his family home in in the tiny town of Brunnwinkl Austria just east of Salzburg and continued his work.

Munich was substantially rebuilt as a result of the Marshall Plan and the Wirtschaft's Wunder (economic miracle) by the time our family spent 12 months there 10 years later in 1954 and 1955. I recall the main nave of the Frauen Kirche and numerous buildings in Munich were still in ruins or under construction. Building cranes had sprouted all over Munich. We did see the famous Trümmerfrauen (rubble women) in action in a few locations pulling brick after brick out of the ruins and stacking them for reuse.

30May1945, Starnberg (just south of Munich), Dear Hanna & Kiddies

Art was in Darmstadt for about two weeks before being transferred to Innsbruck and Salzburg Austria via Munich

Art traveled by Jeep from Darmstadt to Stuttgart and on to Munich. He was amazed by the German Autobahns, the first modern superhighways (the term Art used...like our present Interstates) that did not exist in the US at the time. Much like in the TV Series Band of Brothers, he traveled south on the pavement in his small jeep convoy while legions of POWs and displaced persons, of every nationality were straggling up the median strip and road shoulders in the opposite direction pushing baby carriages, pulling carts, riding heavily loaded bicycles etc. Everything would go smoothly until they hit a big Autobahn bridge or overpass that the Nazi's had blown up to impede the allies, At that point a temporary winding gravel bypass would lead traffic down into the valley across the river on a pontoon bridge and back up to the Autobahn. Many of these detours still existed 10 years later in 1954-55 when our family spent a year in Germany.

On the outskirts of Munich he saw the sign to Dauchau and was fully aware of Nazi treatment of political prisoners and extermination of Jews there. (I visited Dauchau again with my Grandson in 2014). Art reports that the Germans he interviewed were aware of Dachau as a prison camp for political prisoners, but were not aware of the Jewish extermination there and in Auschwitz (in Poland) and the other foreign camps.

Art describes his visit to Hitler's Eagle's nest on June 11th only 35 days after it had been liberated by the US 101st Airborne (Band of Brothers) - See photo in a separate blog post.

Figure 40: Darmstadt in Ruins, May 1945

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

He was billeted in the villa of a former Nazi "bigwig" who had poisoned himself, his grown daughters and their children before the US troops arrived. He slept on a canvas cot under two army blankets and was fed by transient German women. He was still being trained as an interviewer.

"On the way to work we pass along a street where not a single house stands complete" Even so there are Germans living in the city....I don't know where, cellars no doubt. Everyone's clothes are pressed and clean inspite of the dust and rubble surrounding them.

They look well, but no one is fat. Their ration is one wiener-sized piece of meat a week. Professor Kirkpatrick is still with me along with Riegel (German Language Professor from UW) and Workman.

In London, I learned to drive a Jeep and have a license. Also got dog tags like a regular GI

Had a women to interview today with a 3 year old blond boy like Bruce (Art's son of the same age). Sure made me homesick for my little boys (Fritz 5, Bruce 3, Galen & Mark babies), Sylvia (age 9, and my Hanna.

It is too depressing, the tales of these people whether formerly rich or poor... tears at my heart strings. Kiddies are so hungry for sweets and need them."

22May1945, Darmstadt, My dear Hanna (now typewritten)

"In this city there are not only deaths from the front but deaths from bombing. This large city was burned and blasted completely in a 35 minute raid last September. Thousands were burned in their cellars. He relates the story of a man who watched his daughter running towards him, but was consumed by the fire before she could reach him. Inspite of this terror, it is surprising that it did not break their resistance and more surprising that they were able to go about their work within a few days.

It will soon be a month since I left home--- still no mail. I have written every other day since I left. It makes the time go so slowly when I don't hear from you.

17May1945, Darmstadt: Dear Hanna and Kiddies,

(Mostly in Art's handwritten words)

He was billeted in the villa of a former Nazi "bigwig" who had poisoned himself, his grown daughters and their children before the US troops arrived. He slept on a canvas cot under two army blankets and was fed by transient German women. He was still being trained as an interviewer.

"On the way to work we pass along a street where not a single house stands complete" Even so there are Germans living in the city....I don't know where, cellars no doubt. Everyone's clothes are pressed and clean inspite of the dust and rubble surrounding them.

They look well, but no one is fat. Their ration is one wiener-sized piece of meat a week. Professor Kirkpatrick is still with me along with Riegel (German Language Professor from UW) and Workman.

In London, I learned to drive a Jeep and have a license. Also got dog tags like a regular GI

Had a women to interview today with a 3 year old blond boy like Bruce (Art's son of the same age). Sure made me homesick for my little boys (Fritz 5, Bruce 3, Galen & Mark babies), Sylvia (age 9, and my Hanna.

It is too depressing, the tales of these people whether formerly rich or poor... tears at my heart strings. Kiddies are so hungry for sweets and need them."

22May1945, Darmstadt, My dear Hanna (now typewritten)

"In this city there are not only deaths from the front but deaths from bombing. This large city was burned and blasted completely in a 35 minute raid last September. Thousands were burned in their cellars. He relates the story of a man who watched his daughter running towards him, but was consumed by the fire before she could reach him. Inspite of this terror, it is surprising that it did not break their resistance and more surprising that they were able to go about their work within a few days.

It will soon be a month since I left home--- still no mail. I have written every other day since I left. It makes the time go so slowly when I don't hear from you.

I am still convinced that you need to differentiate between the 80,000,000 Germans and the 2-4,000,000 Nazi Party Members."

"This large city was burned and blasted completely in a 55-minute raid last September. Thousands were burned in their cellars. In spite of this terror it is surprising that it did not break their resistance and more surprising that they were able to go about their work within a few days "

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

This picture Art took, best captures the spirit of his stories of arriving in Germany just after WWII had ended. The three little girls are standing with one of Art's colleagues in front of a huge pile of rubble. Each girls is holding something round, an apple maybe? Art always had chocolate and gum for the kids, but not usually fruit. One girls is holding a milk can. When we lived in Munich for a year in 1954-55 we had cans just like that one. There was no prepackaged milk in bottles or cartons, You would take the can to the Milcherei (milk shop), the shop keeper would place it under the spigot and pull down a big lever until the can was full.

This picture Art took, best captures the spirit of his stories of arriving in Germany just after WWII had ended. The three little girls are standing with one of Art's colleagues in front of a huge pile of rubble. Each girls is holding something round, an apple maybe? Art always had chocolate and gum for the kids, but not usually fruit. One girls is holding a milk can. When we lived in Munich for a year in 1954-55 we had cans just like that one. There was no prepackaged milk in bottles or cartons, You would take the can to the Milcherei (milk shop), the shop keeper would place it under the spigot and pull down a big lever until the can was full.

Art arrived in Germany just after many German cities had been totally destroyed by allied bombing. Art shared his K-rations and chocolate with the children. He walked down a street with virtually all buildings destroyed on either side (see Darmstadt description above). Then out of a basement under the rubble, a little girl emerged, perfectly dressed ready to go to church. I didn't see this exact story in his letters, but remember it from "sitting on his knee" at age 5.

Figure 42: Art, Salzburg, 1945

(Salzburg Photo Studio Photo)

Major Hasler, US Army Uniform, taken in a professional photo studio in Salzburg Austria

Art was stationed in Salzburg from June 16 to June 27 1945. Once again extreme luck strikes Art. He is stationed only 27 km and 30 min from Brunnwinkl where his hero, Professor Karl von Frisch, is studying his honeybees.

Figure 43: Art,von Frisch, Wolfgangsee, Austria, June 1945

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

Karl von Frisch and his colleague are wearing the traditional Tyrollean Lederhosen (leather pants (shorts)) worn today mostly by children and waiters in restaurants.

Karl von Frisch, Art Hasler, Brunwinkl, 1945

Galen found this in dad's old lantern slide collection in the Center for Limnology's deep storage facility in Stoughton WI.

His letter of June 17 1945, Art describes traveling from Salzburg only 27 km and 30 min to St Gilgen, Wolfgangsee and Brunnwinkl to visit his idol Professor Karl von Frisch. In a three page typewritten letter he describes in detail, meeting von Frisch and observing him working with his honeybees.

Art was stationed in Salzburg from June 16 to June 27 1945. Once again extreme luck strikes Art. He is stationed only 27 km and 30 min from Brunnwinkl where his hero, Professor Karl von Frisch, is studying his honeybees.

Figure 43: Art,von Frisch, Wolfgangsee, Austria, June 1945

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

Karl von Frisch and his colleague are wearing the traditional Tyrollean Lederhosen (leather pants (shorts)) worn today mostly by children and waiters in restaurants.

Karl von Frisch, Art Hasler, Brunwinkl, 1945

Galen found this in dad's old lantern slide collection in the Center for Limnology's deep storage facility in Stoughton WI.

His letter of June 17 1945, Art describes traveling from Salzburg only 27 km and 30 min to St Gilgen, Wolfgangsee and Brunnwinkl to visit his idol Professor Karl von Frisch. In a three page typewritten letter he describes in detail, meeting von Frisch and observing him working with his honeybees.

Figure 44: von Frisch & Frau,Wolfgangsee, Brunnwinkl, 1955

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

17June1945 Salzburg, Dear Hanna and Kiddies

The picture above of von Frisch was taken 10 years later in 1955, but in this letter Art describes traveling from Salzburg only 27 km and 30 min to St Gilgen, Wolfgangsee and Brunnwinkl to visit his hero, Professor Karl von Frisch. In a three page typewritten letter he describes in detail, meeting von Frisch and observing him working with his honeybees. He had only a beehive, a stop watch, a pan of sugar water and 5 colors to dob on the thorax of the bees. With these primitive tools, his imagination and keen sense of scientific observation he learned enough about bees to win the Nobel Prize.

Figure 45: Letterhead, Nazi Stationary, Innsbruck, June 1945

(Arthur Hasler letter to Hanna)

Looking closer, I see this is a Nazi sticker on UW Madison stationary. Other letters from Innsbruck were on embossed Nazi stationary.

Art was mainly stationed in Innsbruck and Salzburg. Some of his letters from Innsbruck are written on Nazi Stationary. By August 8th he was in London on his way home, he is in NYC on the 10th and after a few days with his sister in NY he was on a plane to Madison. On August 18th he wrote a letter from Madison to his 9-year-old daughter Sylvia who is still in Utah describing his final days in Europe.

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

Art in his army uniform. He had just returned from the war, on August 15.

Sylvia had just returned from two months in Utah with Art's folks and I (AFH) had just celebrated my 5th birthday on August 21

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Back at the University of Wisconsin in Madison

Art starts work on Olfactory Imprinting and Homing of Salmon

Figure 47: Art, Students Madison, 1950

(UW - Madison Archives)

Art and watching his students taking perch out of a gill net on Lake Mendota

Doing fish population studies.

Figure 48: Art, Photometer, Madison, 1950

(UW - Madison Archives)

Art with a photometer on Lake Mendota.

Figure: 49: Lab Boat, ONR Impulse, Madison, 1952

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

Grad students socializing on Lake Mendota

Figure 50: Art, Schmitz, Ragotzkie, Madison, 1953

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

Graduation day - Schmitz gets his Masters and Ragotzkie gets his PhD, University of Wisconsin.

Schmitz would get his PhD from Art in 1958

Figure 51: Homing Salmon, Hasler, Larson, August 1955

(Scientific American Cover)

The Homing Salmon, Hasler and Larson, August 1955

Seminal article in the popular literature on the homing of salmon. Larson, is not a limnology colleague, but a professional science writer that Art hired to make sure that the article, intended for the general public was readable.

Figure 52: Minnow training tank

(Center for Limnology Archives)

A diagram from the article showing how the aquaria were used to ask minnows the question: can you smell very dilute quantities of chemicals and differentiate between water from different lakes?

Figure 53: Art, Wisby, "Weird Science", Madison, 1947

(Center for Limnology Archives)

One of numerous aquaria (Figure 49) that Art used in the old Lake Lab. He used them to prove the sensitivity of fish to the smell of minute quantities of chemicals in the water.

See old lab at the end of Park Street in Figure 12

Figure 54: Art, Wisby, "Weird Science2", Madison, 1947

(Allan T Scholz, Volume 1 Fishes of Eastern Washington)

Figure 55: Art, Warren Wisby, Madison, 1950

(UW - Madison Archives)

Warren observing the minnow responses and Art recording the data.

Figure 56: Art, Sarles, Editors, Madison, 1950

(UW - Madison Archives)

Art with the rows of aquaria used to access a fish's ability to smell, in the old Lake Lab on Lake Mendota at the end of Park Street on the UW campus.

Two Wisconsin daily newspaper editors are shown as they tour the UW Lake Laboratory. Will Conrad, Medford Star News editor, and Charles E. Broughton, Sheboygan Press editor, listen to Professors William B. Sarles and Arthur B. Hasler of the UW Zoology Department talking about fish and lake water.

One of two images. Published in Wisconsin State Journal November 4, 1950.

Figure 57: Diagram of Homing Research Tank

(Homing Salmon, Hasler, Larson, August 1955)

Art's ingenious tank for proving that salmon "home" using the sense of smell. Notice the miniature fish ladders going up the four arms. The next step was to prove it in an actual river system. (Taken from Center for Limnology Archives)

Figure 58: Homing Tank, Madison, 1952

(Center for Limnology Archives)

This is a photograph of the homing tank shown in the diagram in the previous figure.

Off to the State of Washington for an experiment in nature with some big logistical hurdles.

Figure 59: Wisby, Homing Tank, Madison 1952

(Center for Limnology Archives)

Wisby looking into the central holding compartment of the homing tank. Odors are released into the arms. The minnows are trained to swim up the ladders in one of the arms to be fed in response to the odor that is released. The dilution of the odor is continually increased to determined the sensitivity of the minnow's sense of smell.

Figure 60 : Seattle and Issaquah Creek Wiers, 1952

(Imprinting & Homing of Salmon...1983 Hasler/Scholz book)

Map from Wisby/Hasler 1954 Article showing the location of the weirs on Issaquah Creek and the East Fork of Issaquah Creek, East of Seattle Washington. The map shown here is the simplified version used in the 1983 Hasler/Scholz book.

Recalling Art's genius to capture salmon above a fork in a river, take them below the fork, stuff the noses of half of them and release them, capture them again above the fork to prove that only the salmon without stuffed noses could tell which way led to the stream of their birth.

You might guess that Wisby was very instrumental in the whole experiment since he is the first author on the paper. I don't think dad farmed it out to Wisby because he was too lazy to write it up.

This experiment is described in the article:

W.J. Wisby, & A.D. Hasler. (1954) Effect of olfactory occlusion on migrating silver salmon (O. kisutch). Journal of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada, 472-478

If any of the rest of you lay people were wondering what O. Kisutch means:

Species: O. kisutch. Binomial name. Oncorhynchus kisutch (Walbaum, 1792). The coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch; Karuk: achvuun)

If any of the rest of you lay people were wondering what O. Kisutch means:

Species: O. kisutch. Binomial name. Oncorhynchus kisutch (Walbaum, 1792). The coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch; Karuk: achvuun)

Another Interesting Note: A previous experimenter with the same idea in1926, and had severed the olfactory nerves of the altered fish.

However, apparently the fish were so impaired by the surgery that they wouldn't do much of anything.

61: Issaquah Creek Weir Locations

However, apparently the fish were so impaired by the surgery that they wouldn't do much of anything.

61: Issaquah Creek Weir Locations

(Found on the Internet - Text added by AFH)

Figure 62: Area 17 miles East of Seattle

(Google Maps Text added by AFH)

Location where the experiment was conducted

Figure 63: Weir Locations, Issaquah Creek

(Google Maps Text added by AFH)

Weir 1 at the Issaquah State Salmon Hatchery on Issaquah Creek is still in use today although the town of Issaquah has probably built up substantially since 1953

Interestingly the location of Weir 2 - on the East Fork of Issaquah Creek is now in the median of I-90

Figure 64: Wisby, East Fork Issaquah Weir 2, 1952

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

This is the weir 2 (fish trap) built by Art and Warren Wisby on the East Fork of the Issaquah Creek to catch salmon. The salmon were then carried down stream 1.5 miles below the confluence and released. Half the salmon had their noses plugged with cotton. Salmon on the main Issaquah Creek were captured at the Issaquah State Salmon Hatchery (see Figures 64-68).

Figure 65: Wisby, Art, Hanna & Kids, Issaquah, 1951

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

Issaquah and East Fork Confluence

Warren Wisby and Arthur Hasler looking at the confluence of the East Fork of the Issaquah and Issaquah Creek. Art's daughter Sylvia remembers this trip. The women seated is likely Art's wife Hanna, with son Bruce seated beside and Fritz wading in the creek.

I believe downstream is to the left. So Warren and Art would have released the captured salmon in the main Issaquah Creek to our left. The salmon would swim upstream from our left. Of the 27 with unplugged noses that were captured on the smaller East Fork, 19 would repeat the left turn into the smaller East fork while 8 would "mistakenly" continue up the main Creek. Of the 51 salmon with plugged noses only 12 would make the "correct" left turn into the East Fork while 39 would "mistakenly" continue up the main creek

Figure 66: Tagged Salmon, Issaquah Creek, 1952

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

Control Salmon, tagged, but with unplugged nose, ready to be released below the confluence

Figure 67: Wisby, Issaquah Creek, 1952

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

Warren releasing red salmon below the confluence

Figure 68: Results from Wisby Hasler '54 Experiment.

( University Course Viewgraphs: http://courses.washington.edu/fish450/Lecture%20PDFs/home_stray_2.pdf)

Top half: Results from the experiment.

You can see that the unaltered salmon captured on the main Issaquah Creek, on release continued 100% up the creek while none made the left turn up the East Fork.

Of the unaltered salmon captured up the smaller East Fork, on release 70% made the turn up the East fork while 30% continued up the main creek.

Of the salmon captured in the main Issaquah and then had their noses stuffed, on release 76% continued up the creek while 24% made the "false" turn up the East Fork.

Of the salmon captured in the smaller East Fork and then had their noses stuffed, on release 84% "falsely" continued up the creek while only 16% made the "correct" turn up the East Fork.

Although the sample is small, the control group (unaltered) had a very high success rate making the same choice they had made originally, while the altered group (stuffed noses) had a much lower success rate.

Can you imagine the logistics of building the new weir across the whole East Fork, capturing 302 salmon, transporting them down stream, tagging them, stuffing half their noses and releasing them without injury. Then they still had to capture them again to get the results of the experiment.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Bottom Right: A picture of Konrad Lorenz who managed to imprint goslings as hatchlings on himself instead of the mother goose, Result - they are following him around rather than their mother.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Figure 69: Stuffing Salmon Noses, Issaquah, 1953

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

Issaquah Creek, Washington State, from the 1954 Wisby/Hasler article

Original B&W image was found in Art's classic lecture slide carousel

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

As brilliant and elegant as the salmon nose stuffing experiment was, it had several major deficiencies:

1) The sample was small and would need to be repeated to be conclusive.

2) It was not conclusively known whether the salmon were using long term memory from imprinting years earlier as smolts or only short term memory from the part of the stream where they were just captured.

3) It was not conclusively known whether the salmon had been born in these streams or were perhaps straying.

4) It was possible that the nose stuffing had incapacitated the salmon in other ways besides preventing them from using their olfactory capabilities.

For this reason Wisby in a paper he wrote in 1951 proposed an experiment that would involve imprinting baby salmon as smolts with an artificial chemical and attempt to lure them to a stream independent of their birth location. No one took up the challenge until the late 1960s when salmon were introduced into the Great Lakes and Hasler and Scholz set out to conduct the experiment. This experiment is reported later in this blog post.

Figure 70: Salmon, Nose stuffed with cotton, Madison.

(Fritz Hasler Photo)

(Fritz Hasler Photo)

The only color picture I have at present, of a Salmon with a stuffed nose.

From the Limnology Lab Naming Ceremony in 2006 (see Figure 196)

Figure 71: Issaquah State Fish Hatchery, Issaquah, 1951

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

Figure 72: Wier, Issaquah State Fish Hatchery, 1951

(Arthur Hasler lecture slide carousel)

The hatchery in Issaquah Washington on Issaquah Creek served as Wier 1 for the Hasler/Wisby experiment.

The photos below show the hatchery more recently.

From the Limnology Lab Naming Ceremony in 2006 (see Figure 196)

Figure 71: Issaquah State Fish Hatchery, Issaquah, 1951

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

Figure 72: Wier, Issaquah State Fish Hatchery, 1951

(Arthur Hasler lecture slide carousel)

The hatchery in Issaquah Washington on Issaquah Creek served as Wier 1 for the Hasler/Wisby experiment.

The photos below show the hatchery more recently.

Figure 73: Salmon Jumping, Issaquah Creek Hatchery

(Found on the Internet)

Salmon Jumping, Issaquah Creek Hatchery , Washington Sate

Salmon jumping up small dam at the Issaquah State Salmon Hatchery, 17 miles east of Seattle on Issaquah Creek. Salmon swim up the Issaquah creek and are caught in the Hatchery. In the Hatchery, they are killed for their eggs and sperm, which are used to hatch more salmon.

Figure 74: Issaquah State Salmon Hatcher, Issaquah Creek

(Found on the Internet)

Note: Sluice gate/fish ladder on right where some salmon climb right into the hatchery to be caught (see next photo)

Figure 75: Catching Salmon, Issaquah Creek Hatchery,

(Found on the Internet)

Half the salmon in Wisby and Art's experiment described in the 1954 article were caught at this Washington State Salmon Hatchery on Issaquah Creek.

Figure 76: Salmon below dam, Issaquah Creek Hatchery

(Found on the Internet)

Note: One salmon on far left trying to jump the dam - Issaquah State Salmon Hatchery on Issaquah Creek

Figure 77: Salmon Spawning

(Found on the Internet)

Salmon that make it back to their birth stream turn red as a result of exposure to fresh water.

Figure 78: Salmon Spawning

(Found on the Internet)

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Back at the University of Wisconsin in Madison

Figure 79: Art, Fisherman, Madison, 1954

(UW - Madison Archives)

Limnology research wasn't just summer fun! Art and his crew also did a lot of research in the winter.

Art with a local fisherman during a creel (population) census on Lake Mendota about 1954

Fishing for perch through a hole in the ice is a popular winter pastime in Wisconsin.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Art's Public Service Work

Figure 80: Proposed Parking, Wisc S Journal, Madison, 1954

(UW - Madison, Archives)

Article in the Wisconsin State Journal on a proposal to construct a 470 car parking lot on fill on the shore of Lake Mendota just west of the Memorial Union. Art vehemently opposed the plan which would have been located right where the new Limnology Lab was eventually built in 1962.

In addition to his work killing the proposed parking lot in Lake Mendota, Art work tirelessly over many years to cleanup the Madison lakes.

Madison is located on an Isthmus between Lakes Mendota (see above) and Monona.

Madison is located on an Isthmus between Lakes Mendota (see above) and Monona.

When Art arrived on the UW campus as an instructor in 1937, Lake Monona and Waubesa (the lake below it in the chain) were a cesspool, totally infested with algae due to the fact that Madison sewage had been pumped directly into lake Monona. Mendota was better, but was often overgrown with weeds due runoff from farmers fields and the effluent from two smaller upstream towns.

Art worked throughout his career, to stop the poisoning of the algae with copper sulphate, and getting the sewage from Madison and upstream towns routed around the lakes.

Figure 81: Algae Bloom, Yahara River, Madison, 1945

(UW - Madison Archives)

Before Art and others got the sewage rerouted, the lakes down stream from Madison; Monona and Waubesa, and the Yahara River connecting them, were a cesspool, totally infested with algae due to the fact that Madison sewage had been pumped directly into lake Monona until 1936 and Waubesa until 1958.

Source: Perspectives on the eutrophication of the Yahara lakes by Richard C. Lathrop (Published online 29 Jan 2009) at http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07438140709354023

Figure 82: Young lady entangled in weeds, Madison, 1954

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

Art was a master of public relations. Here he uses an attractive young women to dramatize the disgusting nature of the weeds growing in eutrophicated (too many nutrients) lakes.

Figure 83: Weed harvester, Madison

(Center for Limnology Archives)

One of the weed harvesting machines that Art advocated using rather than poison to deal with the nutrient rich lakes around Madison.

Figure 84: Weed Harvesting on Madison Lakes

(Found on Internet)

Figure 85: Hasler Boys Whaler, Lake Mendota, Madison

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

Art's photo of the family boat showing that Lake Mendota still had a problem with algae blooms in 1963.

The waste water from upstream communities was not diverted until 1971. Even after the diversion, eutrophication is still occurring due to runoff from fertilizer from lawns and farmers fields.

Source: Perspectives on the eutrophication of the Yahara lakes by Richard C. Lathrop

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Art takes Fulbright Professorship Year in Munich Germany and takes the whole family along

Figure 86: Art with Professor von Frisch, Munich, 1954.

(Center for Limnology Archives)

Art takes a Fulbright professorship in Munich and brings the whole family of eight to Germany for a year.

Karl von Frisch was the Nobel Prize winning honey bee researcher that Art had met in Austria in 1945. From family memories: von Frisch's children said they would have starved to death if Art hadn't smuggled food to them right after the war. By now, Art had figured out that salmon find their way back to their birth stream, using their sense of smell. At this point he was trying to find out how the salmon find their way in a huge ocean, back to the mouth of the correct major river. Navigation using sun or stars?

Figure 87: von Frisch, Brunnwinkl, 1954

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

von Frisch abandoned his home in Munich during the War and moved back to his family home in Brunnwinkl Austria on beautiful Wolfgangsea to avoid the heavy bombing of the city. Art found him here when he looked him up when he came as part of the Strategic Bombing Survey in 1945. Art kept up the relationship sending food at first, then helping von Frisch obtain chemicals and scientific equipment that was not available in Europe right after the war. von Frisch is wearing the hearing aid that Art got for him when he found out that he was hard of hearing.

Figure 88: von Frisch and Lorenz, 1955

(Magnuson View Graph)

Konrad Lorenz was another of dad's colleagues that he visited during the year in Munich. The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1973 was awarded jointly to Karl von Frisch, Konrad Lorenz and Nikolaas Tinbergen.

-

Figure 89; Konrad Lorenz, Geese Imprinting, 1955

(Arthur Hasler Lecture Slide Carousel Photo)

Figure 90: Haslers, Munich, August 1955.

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

Karl (named after Karl von Frisch), Mark, Galen, Bruce, Fritz, Sylvia, Hanna, Art

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

Karl (named after Karl von Frisch), Mark, Galen, Bruce, Fritz, Sylvia, Hanna, Art

Along with his professional career, Art was a husband and the father of 6 children. Here is the whole family as they were leaving Munich after Art had been doing a year of research with Professor von Frisch.

Haslers “Departure from Munich” in the back yard of the Kunigundenstrasse 55, house in Munich Germany just before they returned to the States in August of 1955. Note: family members are wearing large pretzels around their necks and three of the boys are wearing Lederhosen (leather pants)

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Back at the University of Wisconsin in Madison

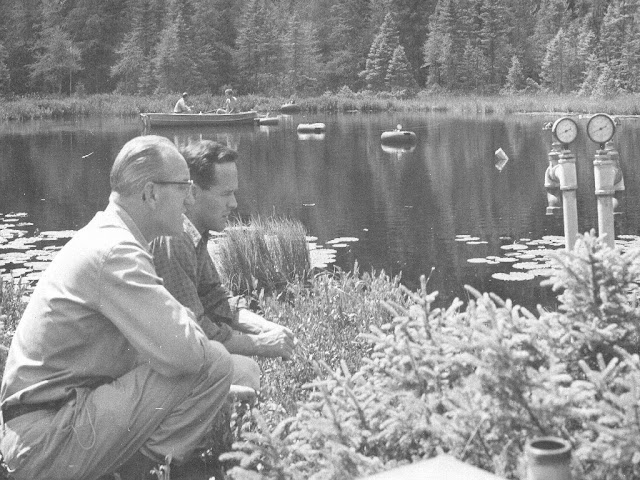

Fig. 91: Art, Wisby, Colleague, Homing Tank, Madison, 1957

(UW-Madison Archive)

(UW-Madison Archive)

Figure 92: Art, Braemer, Homing Tank, Madison, 1957

(UW-Madison Archives)

In this picture, Art is talking to visiting scientist Wolfgang Braemer about the homing tank shown in this picture at the lab on Lake Mendota in 1957. I remember dad having a similar tank in Munich in 1954, but it was indoors and he used lamps to simulate the sun.

Figure 93: Old Lake Lab, Madison, 1957

(UW-Madison Archives)

This is the lab that Art used with his graduate students when he came back from Virginia in 1937 until the construction of the new Limnology Laboratory in 1962. We see it here, at it's peak, with a big platform on the end of the pier for the big fish homing tank (see Figure 84 above) and other tanks.

The memorial Union is on the left with Hoofers student recreation club canoes on the shore. The temporary quonset hut on the right is one of numerous huts built all over the UW campus during WWII in the 1940s. The last ones were not replaced with a permanent buildings until the 1990s. The zoology department used quonset huts for many years.

Figure 94: Art, with Students, Madison, 1957

(UW-Madison Archives)

Art, Ragotzkie, Horall, von Frisch, Wisby, Madison, 1957

Bob Ragotzkie with SCUBA gear on ladder, Ross Horall with earphones, Otto von Frisch (son of Karl) with flipper & SCUBA gear, Warren Wisby in Cabin, Art holding light cord.

Art got significant grants of money and equipment from the Office of Naval Research (ONR) the boat, the IMPULSE was a surplus Naval vessel supplied by ONR. Sonar gear, and probably the SCUBA gear came from ONR as well.

Figure 95: ONR Impulse, Old Lake Lab, Madison, 1957

(UW-Madison Archives)

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Art and Colleagues begin Whole Lake Experiments

Figure 96: Art with Bill Schmitz, Saw Mill Pond, 1956

(Center for Limnology Archives)

Trying to use air bubbles to turn over a lake on the Guido Rahr Property on the Wisconsin/Michigan border. Now part of the Tenderfoot Forest Preserve.

Figure 97: Art with colleague Schmitz, Saw Mill Pond, 1956

(Center for Limnology Archives)

Figure 98: Schmitz, Saw Mill Pond, 1956

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

Figure 99: Hanna, Boys, Schneider, Madison, 1956

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

Hanna, Hasler boys, VIP Zoology dinner guest, Hans Schneider from Germany, eating Christmas turkey, Hasler home 205 Lathrop St.

Schneider wrote a paper on Grunion sounds related to migration.

Hanna served dinner to a countless number of Art's visiting guests at the Hasler home in Madison.

Art is the photographer taking the picture with his Leica camera and flash.

(Magnuson Viewgraph)

Liming Lakes over the years, Northern Wisconsin 1933, 1956

On the left, Art with Hugo Baum building lime floats at Trout Lake in 1933

Figure 101 Art's son Fritz, Liming Peter Lake, 1956

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

Classic Limnology Lab picture on how to change the chemistry of a lake. Identical Paul lake was left untouched as a control.

Figure 102: Fritz, Liming Peter Lake, 1956

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

That's me above (Art's eldest son Fritz) emptying a 50 lb bag of lime into a basin, I'm about 16 so this is actually about 1956. In Figure 92 on the left, Art with Hugo Baum building lime floats at Trout Lake in 1933. I'm thinking that both methods have the same goal, but obviously doing it with a high volume motorized pump will get dissolved lime into the water a whole lot quicker.

Figure 103: Fritz, Liming Peter Lake, 1956

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

In this picture you can see a tub outside the boat where Fritz is dumping the lime. A big white hose carries the limey water to the pump that shoots it out the back of the boat

The driver is operating a 5 hp outboard motor to move the boat.

Figure 104: Peter & Paul Lakes.

(Found on the Internet)

Peter & Paul Lakes that "looked like an hour glass or a pair of spectacles" with a narrow passageway between them. Art got permission to use a bulldozer to make one lake into two. Experiments were conducted on Peter (right?) and Paul (left?) remained untouched as a control.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Although Art worked tirelessly to protect the Madison Lakes from effluent nutrient pollution, copper sulphate poisoning of algae, and land fill, he was not afraid to "mess with mother nature" to advance scientific knowledge of lake systems.

The liming of lakes shown above, turning over lakes with compressed air shown earlier, the introduction of radioactive radioisotopes in the 1960s, the acidification of lakes with sulphuric acid by his successors in the 1980s were all examples of the Hasler whole lake experiment approach.

He used bulldozers to divide one lake into two and to make ponds in the UW Arboretum for experiments. At one point he even dynamited the UW Arboretum in a failed attempt to make a pond.

You might say he used nature like a kid using a chemistry-set for doing experiments. Most of these experiments could never be approved under current EPA and DNR rules and will never be repeated.

In his defense, these were all small scale modifications of nature and will have no lasting significant effect.

Figure 105: Three of Art's sons, Trout Lake Camp, 1958

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

Karl, Galen, Mark

This was one of the historical Trout Lake Camp cabins used already in the 1930s but now long gone since the building of the new Trout Lake Lab in the 60s.

Figure 106: Art, Lab Coat, Madison, 1958

(Center for Limnology Archives)

Almost luminescent!

Figure 107: Art, Tibbits, Large Mouth Bass, Madison, 1958

(UW-Madison Archives)

Big fish in a small tank

Figure 108: Art, Students, Old Lake Lab, Madison, 1960

(UW-Madison Archives)

Figure 109: Art with Hawaii Dolphin 1960

(Center for Limnology Archives)

Figure 110: Art, Passport Photo and Stamps, 1961

(Center for Limnology Archives)

Art, the well traveled Scientist

Figure 111: Anderegg, Art, Stewart's Dark Lake, 1969

(UW-Madison Archives)

John Anderegg and Art preparing "hot" radioisotope for insertion into the lake.

Figure 112: Art, Anderegg. Likens, Stewart's Dark Lake, 1960

(Breaking New Waters/Center for Limnology Archives)

John Anderegg, Gene Likens, and Art holding a scintillation counter used for the detection of isotopes in a study of the movement of radioactive nuclides from the bottom of a stratified lake.

Paraphrasing from a conversation with Gene in 2016: "We were investigating the implications of a proposal to put radioactive waste in deep ocean trenches. This lake was very stratified and didn't turn over. We put these dangerous hot isotopes on the bottom of the lake. Coming back later we found organisms on the shoreline that had ingested the isotopes on the bottom, brought them to the top and were still very "hot". It would have been a very bad idea to put nuclear waste deep in the ocean........

At one point when I was taking the hot radio isotopes out of their lead container and was about to put them into the water, Art said "hold a second while I take a picture" however, not wanting to overexpose my self to radiation, I put them immediately into the water."

Gene Likens wrote the biography of Art that is included at the end of this blog post.

Likens became a professor at Dartmouth College and Cornel University and was later the director of the New York Botanical Gardens. He is famous for discovering Acid Rain and received the National Medal of Science from President George W. Bush

Likens was born in 1935

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Art Hosts the 15th International Conference of Limnology at the University of Wisconsin in Madison

Figure 113: Art, Ragotzkie, Madison, 1962

(UW-Madison Archives)

Lake Mendota, Picnic Point in background

Prior to the 15th International Congress on Limnology, Profs. Robert A.

Ragotzkie (left), local chairman, and Arthur D. Hasler (right), executive chair of the congress, inspect yellow lotuses on Mendota Bay near

the willows.

Figure 114: Art, Hosting the SIL Meeting, Madison, 1962

(Center for Limnology Archives)

Art, Hosting the International Society of Limnology Meeting, Madison, 1962

This was the 15th SIL and the first time it was held in the US.

UW Student Union Terrace, with Hoofers boats in background.

Paraphrasing from Art's oral history: "I got a grant from the National Science Foundation to sponsor this event. It allowed me to hire an Executive Director for a year and to charter a flight from Europe to bring over the best scientists. European scientists had to apply for the travel grant and we picked the ones we thought would make the biggest contribution to the meeting."

Figure 115: Art, Ragotzkie, Float Plane, Madison, 1962

(Center for Limnology Archives)

Art was always using the latest technology, You could use a float plane to get into a lake in Northern Wisconsin that you couldn't access otherwise. Probably Mendota on Picnic Point, considering the UWZ boat on the left.

Figure 116: Art, Ragotzkie, Float Plane, Madison, 1962

(UW-Madison Archives)

The float plane belonged to the Department of Meteorology.

Art frequently worked together with departments beyond his home Zoology Department.

His son Fritz received his PhD from the UW Meteorology Department in 1971 and went on to a 30 career at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. This blog post is a retirement project of Fritz, where he has put his image processing and computer skills to use.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Art Builds the Laboratory for Limnology at UW Madison and Trout Lake Station

Figure 117: Laboratory for Limnology, Madison, 1962

(Found on the Internet)

(Now Arthur D Hasler) Laboratory for Limnology

(Found on the Internet)

(Now Arthur D Hasler) Laboratory for Limnology

Art wrote the proposals and received funding from the National Science Foundation to build the Laboratory for Limnology at the University of Wisconsin in 1963.

Once the bids came in for the unique cantilever design, he was very disappointed that the size of the lab had to be reduced to meet budgetary constraints.

(Arthur Hasler Lecture Slide Carousel)

Figure 119: Boat Basin, Limnology Lab, Madison

(Fritz Hasler Photo)

A great place to keep the boats indoors in the new lab. (taken 2006 at the naming ceremony)

The Hasler boys were the first to buy a Boston Whaler. They teamed up to buy a 12' 2" Boston Whaler with a 50 hp Mercury outboard for water skiing in 1963 about the time the new lab was finished

Laboratory for Limnology Leaders:

Art Hasler 1963 - 1978

Magnuson 1978 - 2001

(Founding director of the Center for limnology

(Founding director of the Center for limnology

Jim Kitchel 2001 - 2009

Figure 120: Magnuson, Carpenter, Kitchel, Madison, 2009

(Center for Limnology Archives)Art's successors

Figure 121 Trout Lake Station Boulder Junction, 2016

(Aerial photo provided by Carol Warden)

Art also secured the initial Stage 1 funding in 1967 for the Limnology Station on Trout Lake, North of Minocqua WI.

Stage 1 is the part of the building closest to the Lake.

Stage 2 (the new wing at right angles to stage 1) was built in 1985 and dedicated in 1989

Stage 3, built in 2012 (with the Juday conference room) is the section of the building farthest from the lake with the lighter roof.

The Tom Frost House (adjacent but not shown) was built in 2009. It is used to house visiting scientists.

Stage 1 is the part of the building closest to the Lake.

Stage 2 (the new wing at right angles to stage 1) was built in 1985 and dedicated in 1989

Stage 3, built in 2012 (with the Juday conference room) is the section of the building farthest from the lake with the lighter roof.

The Tom Frost House (adjacent but not shown) was built in 2009. It is used to house visiting scientists.

Figure 122: Trout Lake Station Boulder Junction, 2016

(Photo provided by Carol Warden)

(Photo provided by Carol Warden)

The section on the left with the entrance, houses the new conference room.

Figure 123: Old Labs at New Trout Lake Station, 2016

(Fritz Hasler Photo)

Susan Knight (Interim Director), ????, Fritz Hasler

Old Labs at the Trout Lake Station, Boulder Junction WI 2016

When the new lab was built in 1967 the old cabin labs, some built as early as 1926 were moved across the Lake on the ice to the new lab location. In 2016 the old labs are in great shape and look like they could have been built yesterday.

Figure 124: Laboratory for Limnology, Madison, 1963

(Magnuson Viewgraph)

Figure 125: Art, Clifford Mortimer, new lab, Madison, 1963

(Center for Limnology Archives)

Figure 126: Art with Mortimer, New lab, Madison, 1963

(Center for Limnology Archives)

Mortimer was a visiting physical limnologist originally from the U.K. who had studied in Berlin Germany. He was later a professor at UW Milwaukee.

Figure 127: Art, Limnology Group, Madison, winter 1964

(Center for Limnology Archives)

Art far left.

Figure 128: Art, Henderson, Chipman, Madison, 1965

(Center for Limnology Archives)

Francis Henderson seated, Gerald Chipman standing on Lake Mendota

Tracking fish that have been released with inserted miniature transmitters.

Figure 129: Art, Henderson, Madison, 1965

(Center for Limnology Archives)

Henderson holding a miniature ultrasonic transmitter to be stuffed into the mouth or anus of a fish (according to son Galen) so that it could be tracked (see previous figure)

Figure 130: Art, Zoology Faculty, Madison, 1966

(Center for Limnology Archives)

Art upper left in front of Birge Hall

Figure 131: Scherzl, Madison, 1965

(Arthur Hasler Photo)

As you would expect, Art was an excellent fisherman. Whether he was casting for walleye, dropping a line for perch or fly fishing on the Brule or the Yellowstone, he could do it all.